How The Titanic Actually Sank?

On April 10, 1912, the most famous ship in the world sets sail and we all know how that story ends. For years, the villain of the Titanic story was a rogue iceberg, lurking in the dark off the coast of Newfoundland. The initial investigations placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Titanic’s captain, E. J. Smith, accusing him of the reckless act of charging through an ice field at almost 22 knots in the dead of night. But that’s not why the Titanic sank. Not the only reason.

The Truth About the Titanic: 11 Important Questions

Let’s explore the details of an ill-fated journey that started with the construction of the Titanic and ended with it on the bottom of the ocean. We’ll answer all the important questions, starting with the engineering of the ship to how the crew acted on that ill-fated night.

1. Was the Titanic as great as it was advertised?

On the day it left its construction site, in Queen’s Island, now known as the Titanic Quarter in Belfast Harbour, the Titanic was considered an emblem of technological triumph and human aspiration. On its maiden voyage, this colossus of the sea carried more than 2,200 souls, and each one of them was convinced that the ship was invincible.

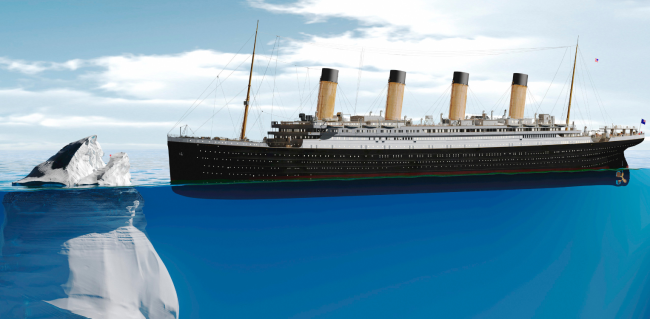

And they had every right to believe so. When it was launched, the Titanic dwarfed all that had come before it. This sea marvel was the largest ship afloat, measuring an astounding 882.5 feet in length, 92.5 feet in breadth, and 175 feet in height. Displacing more than 50,000 tons of water, the Titanic was, quite simply, the most massive movable object ever crafted by human hands. This feat of engineering was not just about size; the ship was a testament to the turn-of-the-century technology. It was equipped with newly-designed watertight compartments that could be sealed off in the event of a punctured hull. Yet, they had a major design flaw that we will look into later on.

Apart from the sheer size and technology, the Titanic was also an oasis of luxury and comfort. The ship featured a gymnasium, swimming pool, libraries, high-end restaurants, and cabins that dripped with luxury. The passenger list for the Titanic’s maiden voyage read like a page of “Who’s who of the world’s wealthiest individuals?”.

So, the headlines had been big, the advertising from the ship’s owner, the White Star Line, clear – The Titanic was unsinkable. Yet, just four days after it set sails on its maiden voyage, this ‘unsinkable’ marvel of engineering would lie at the bottom of the North Atlantic, taking with it more than 1,500 lives.

Of course, you could argue that no ship is really unsinkable. But still, why did the Titanic succumb to the sea in less than three hours? The ship’s builders had previously claimed that even under the most critical conditions, the Titanic should have stayed afloat for a minimum of 2 to 3 days.

That obviously didn’t happen. So, let’s take a closer look at its short, ill-fated voyage.

2. What happened on the night of April 14th?

On the fateful night of April 14th, despite receiving multiple warnings about ice, the Titanic continued to cut through the dark North Atlantic waters at almost full speed. Tragically, by the time the lookouts spotted the colossal iceberg, it was barely a quarter of a mile away from the ship’s front, making a collision inevitable.

Despite immediately reversing the engines and steering hard to the left, the colossal mass of the Titanic meant it needed a vast distance to slow down and alter its course. With the iceberg looming so close, there wasn’t enough space.

The Titanic didn’t hit the iceberg head-on, but rather scraped against it, damaging almost 100 meters of the hull above and below the waterline on the right side. This encounter was enough to breach six of the main watertight compartments. Water started rushing into the bow of the ship, causing it to tilt downwards and slightly to the right.

Picture a seesaw. If both sides get heavily weighed down, and the bar in the middle isn’t strong enough, it’ll break. This is essentially what happened to the Titanic. As the front of the ship dipped further into the water, the back end, heavy with three large propellers, started lifting out of it. When the strain on the middle part of the ship exceeded the strength of the steel it was made of. The result was catastrophic – the Titanic almost broke in half, right down the middle.

This, in essence, is how the ‘unsinkable’ Titanic sank. Now, let’s look at the main engineering flaws and human errors that led to this disaster.

3. Did the watertight compartments make things worse?

While the Titanic’s design was groundbreaking for its time, it was far from perfect. The claim of the ship being unsinkable rested largely on the supposed ‘watertight’ compartments in its lower section. However, these compartments were only watertight horizontally, not vertically.

Here’s what this means: The Titanic’s lower section was divided into 16 major compartments, each designed to be sealed off if the hull was damaged and started taking on water. But, and this is crucial, the tops of these compartments were open. Their walls extended just a few feet above the waterline.

While these partially sealed compartments were not the sole reason for the Titanic’s sinking, they did play a part in it. If the compartment walls had been built taller, extending well above the waterline, they could have better contained the incoming water within the damaged areas. This modification might not have prevented the sinking, but it could have bought the ship some precious time, possibly long enough for help to arrive from nearby vessels.

Now, when the iceberg damaged the hull, six of these sixteen compartments were breached, and they were immediately sealed off. But as these compartments filled with water, the weight caused the ship to tilt forward, and the water began to spill over into the neighboring compartments due to their open tops.

This is where the irony lies: the very design feature meant to keep the ship afloat – the watertight compartments – actually sped up the disaster. Instead of spreading out evenly, the water was trapped in the bow of the ship due to these compartments, pulling it down faster.

4. Was the Titanic hull too fragile?

Pieces of the Titanic’s hull were retrieved from the ocean floor and underwent rigorous testing, providing vital clues to understanding why the ship sank so quickly. The tests revealed that the steel used for the Titanic’s hull was quite brittle. What does this mean? When the Titanic’s hull hit the iceberg, the hull should have deformed, absorbing a bit of the impact. Instead, it fractured into pieces.

Scientists conducted an experiment on small pieces of the Titanic’s steel, alongside modern, high-quality steel. Both samples were chilled to mimic the freezing conditions on the night of the disaster. Under impact, the modern steel bent, while the Titanic steel simply shattered. There was no bending or deformation.

Moreover, some of the recovered steel from the Titanic was found to contain high levels of oxygen and sulfur, indicating it was semi-kilned, low-carbon steel, produced using the open-hearth process.

Examined under a powerful microscope, the steel displayed a grain structure. The high sulfur content within the steel disrupted this grain structure, escalating its brittleness. When sulfur within the steel combined with magnesium, it formed pathways of magnesium sulfide, which essentially served as ‘highways’ for crack propagation. While many steels used for shipbuilding in the early 20th century had elevated sulfur levels, the sulfur content in Titanic’s steel was extraordinarily high even by those standards.

5. Were the Titanic materials low-quality?

The Titanic, like all ships, was held together by rivets, special nails that fastened the ship’s body, or hull plates, to the main structure. More than 3 million rivets were used in the Titanic, but they turned out to be one of the ship’s weak links.

The White Star Line shipbuilders, pressured to build three massive ships simultaneously, resorted to lower-quality iron rivets to save time. These inferior rivets, prone to breakage, were used especially in the bow and stern, which are the ship’s front and back parts. In these parts, the larger machines couldn’t reach to install the stronger steel rivets. So, the midsection of the ship benefited from the use of tougher steel rivets, but not the front and back.

When the Titanic crashed into the iceberg, the force was too much for the weaker iron rivets, especially at the bow. The cold temperature that night made the rivets brittle, like a stick that easily snaps in winter, and they popped or broke under impact. This led to the hull plates parting at the seams, creating openings for water to flood the ship, accelerating its sinking.

Even rivets not in direct contact with the iceberg felt the catastrophe’s effect. As water gushed into the Titanic, it applied pressure on the cracked hull plates’ edges, affecting the rivets along the seams. They too stretched or broke, providing more inlets for the rushing water.

Interestingly, researchers observed that flooding ceased where the ship’s stronger steel rivets began. This demonstrates the crucial role rivet quality played in the Titanic’s rapid sinking. When it was most needed, the “glue” holding the Titanic together failed, highlighting the rivets as a potentially critical factor in the ship’s tragic demise.

6. Did the Titanic receive any iceberg warnings?

Yes, it did. It seems the Titanic received multiple iceberg warnings on the day of the collision and before that, but they were not given the level of attention they perhaps deserved.

You see why the story of the Titanic is more than just a tale of an iceberg and a sinking ship? It’s because it speaks of human courage and folly, ambition and hubris, loss and survival. There was a cascade of events that led to the Titanic’s ultimate demise.

But, to get back to our Captain and the multiple iceberg warnings, you see, everyone on board the Titanic was excited, overflowing with confidence.

And there were also distractions. Not a Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet making out type of distraction, but still.

For example, the ship’s wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were employed by Marconi Company and their primary responsibility was to relay messages between passengers and the mainland. But at that time, there wasn’t a standardized system for prioritizing incoming wireless messages. The iceberg warning from the other ships could have been cut off by the Titanic’s operators due to the volume of passenger messages they were dealing with.

Some of the iceberg warnings did reach the bridge officers, but the gravity of these warnings may not have been fully understood or taken seriously enough. Also, it was common for transatlantic voyages to encounter ice and they often relied on lookouts to spot any danger well in advance.

7. So, why didn’t they spot the iceberg earlier?

The night the Titanic struck the iceberg was moonless and exceptionally calm. While this may sound like ideal conditions for a voyage, the calmness of the sea actually made it harder to spot icebergs. When waves hit an iceberg, they create a breaking water line that is easier to see. On a calm night, this visual clue isn’t there, making icebergs harder to detect.

Moreover, the lookouts in the crow’s nest didn’t have access to binoculars. Apparently, the locker containing the binoculars was locked, with the key held by an officer who was no longer on board. How about that?

However, debate exists over whether binoculars would have helped the lookouts spot the iceberg earlier, given the limited field of vision binoculars provide.

On another hand, some researchers have proposed that atmospheric conditions on the night of the disaster might have caused a mirage effect, refracting or bending the light in such a way that the iceberg was camouflaged against the horizon until it was too late.

Could we call all of these a tragic coincidence? But wait, there’s more!

8. When did they realize the ship was going to sink?

It wasn’t right away, that’s for sure!

When the Titanic first struck the iceberg, the severity of the damage was not immediately apparent to everyone on board, including Captain Edward Smith and the ship’s officers. This delay in comprehension of the severity of the situation contributed to a delay in sending out distress signals.

Additionally, there was also some initial confusion about the most effective way to ask for help. In 1908, an international maritime agreement had established “SOS” as the standard distress signal. However, many operators continued to use the older “CQD” signal. Initially, the Titanic’s wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, sent out “CQD” messages. At one point, in a somewhat ironic exchange, Bride jokingly suggested to Phillips that he should use the new “SOS” signal, as it might be his last chance to use it. Phillips then began to alternate between “CQD” and “SOS”.

Another factor was that the wireless equipment of the time was not as reliable or as powerful as modern communication systems. The distress signals were not picked up by all ships in the area, and the nearest, the RMS Carpathia, was almost 4 hours away at full steam.

9. Is it true that they were going too fast?

It’s like you buy a brand-new Ferrari and you go driving with the top down through a beautiful winding road. You’re not really thinking of any possible dangers along the way. You’re just enjoying the ride. So, maybe people on board the Titanic were also experimenting this exhilarating feeling. Plus, they were travelling on the largest man-made movable object of that time. The Titanic might have appeared huge to them in comparison to any iceberg or force of nature.

Let’s not forget that the people on board believed the ship was virtually unsinkable, which could result in a false sense of security and a willingness to maintain high speeds even in potentially dangerous conditions. Moreover, there was also the pressure of adhering to their advertised schedule, and maybe even arriving ahead of time.

There was also an underestimation of the risk associated with icebergs. The prevailing wisdom at that time was that icebergs posed little threat to large vessels, which were thought to be capable of withstanding a collision.

10. Is true that a fire weakened the bulkheads?

There’s indeed evidence that a fire broke out in one of the Titanic’s coal bunkers approximately 10 days prior to the ship’s departure. The fire wasn’t fully extinguished until a few days into the voyage. However, we can’t really make the claim that the fire weakened the ship’s hull or bulkheads to a degree that significantly contributed to the disaster.

Historically, coal bunker fires were not uncommon, particularly with the type of coal used during that period. The crew would manage such fires by attempting to remove and use the burning coal as quickly as possible. In the Titanic’s case, the fire was managed in a similar manner.

Some researchers suggest that the fire, located in a bunker of boiler room 6, could have weakened the steel hull structure and bulkhead, making it more susceptible to damage upon hitting the iceberg. However, this theory is somewhat contested. Most experts agree that while the fire likely didn’t help the situation, the primary cause of the disaster was the collision with the iceberg and the subsequent failure of the watertight compartments to contain the flooding.

However, the role the coal fire played in the disaster is still a matter of ongoing debate among historians and researchers.

11. Why weren’t people trained on how to react in such situations?

Well, we’re talking about the early 1910s. The crew was not sufficiently prepared to handle a crisis of the magnitude that unfolded after the iceberg collision.

As you all know by now, the lifeboats onboard the Titanic were not used to their full capacity. In fact, they could collectively carry only about half of the total people onboard. But even so, many were launched without being filled to their own individual capacities, leading to even more loss of life.

Moreover, it also seems that Captain Edward Smith cancelled the lifeboat drill that was scheduled for the very day the Titanic struck the iceberg. The reasons behind this decision remain unclear, though some speculate it was due to the cold weather or the observance of a church service.

We don’t think that a simple lifeboat drill might have educated people, but maybe it would have helped to some degree. The lifeboat drill would probably have familiarized the crew and passengers with the procedures of loading and lowering the lifeboats.

In the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, numerous investigations were launched. Boards of inquiry interviewed witnesses and experts, looking into everything from the crew’s conduct to the ship’s construction. This long analysis sparked a range of theories about the ship’s fate, as we’ve seen so far- brittle steel plates, popped rivets, or failed expansion joints.

Yet, beyond these technical aspects, the Titanic’s story became a parable of human arrogance. Deemed unsinkable, the ship’s downfall stunned the world. Early reports of those days mistakenly suggested that the Titanic had merely collided with an iceberg and was being towed to safety. As the horrific truth unfolded, the loss of over 1,500 lives on the ship’s maiden voyage sent shockwaves across the globe.

Drawing parallels with the 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster, historian John Maxtone-Graham highlighted the harsh reality of our technological failings. Both tragedies demonstrated how symbols of human ingenuity could abruptly meet their end, serving as stark reminders of our vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, the tale of the Titanic reverberates through time, embodying the clash between human ambition and nature’s might, and reminding us of our limitations in a world still ripe for exploration and understanding.